CONNECTICUT SHADE LEAF

featuring

John Bailey Stewart and Marcus Floyd

RED TEXT: the writer’s words my emphasis

BRACKETED TEXT [[my additions]]

On September 15th, 1875, John Bailey Stewart became the 6th of 9 children born to Mary Hubert and her Canadian-born husband, Charles Stewart, a Caseville, Michigan, farmer. Young John quickly adapted to farm operations, and with strong family encouragement ultimately set off to Michigan State University to specialize in scientific soil analysis and management as well as the latest techniques in plant cultivation.

Upon graduation in 1901, at age 26, John was hired by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Washington to be part of a national soil survey, to identify the type of soils throughout the United States and make suggestions as to the most useful or profitable way to use those soils. If it were to be agriculture, what specific crops would be most suitable to plant.

The quality of Stewart’s analyses, reports and recommendations for Texas and other States resulted in the widespread publication of his data, as well as personal recognition within the excellent USDA as one of its rising stars. He was promptly promoted. Stewart requested to research the Connecticut Valley shade leaf industry.

An 1896 USDA Bulletin described the light sandy soil along the Connecticut River to be very much like the soils in which high priced wrapper-grade Sumatran tobacco was grown.

In 1899 the US Department Agriculture sent the Department’s top tobacco expert, Milton L. Floyd, to help study fermentation methods.

Another of Floyd’s duties was to do a detailed analysis of 400 square miles of Connecticut Valley soil from South Glastonbury, Conn., to South Hadley, Mass. Floyd explained the reason behind the Survey:

“Connecticut tobacco is worth, on an average of 18¢ -20¢ per pound; Sumatran tobacco imported exclusively for wrapper purposes pays a duty of $1.85 a pound and sells on the market for $2.50 to $3.00 per pound duty paid. The Connecticut leaf is too large for an ideal wrapper being often 26” to 30” long. [[ ideal was 14”-16” long]]

The veins are very large and only the tip of the leaf is suitable for high price cigars. The desirable grain, color, and style are confined to the tip of the leaf, the lower half being glossy and very undesirable for wrapper purposes. This makes a great deal of waste, which can only be marketed in foreign countries at an exceedingly low price. Lastly, the tobacco is more highly flavored than is desirable for wrapper purposes... These defects , as already stated, are to be made the subject of an exhaustive inquiry of the Division of Soils.” Milton Floyd on what the USDA was doing and why.

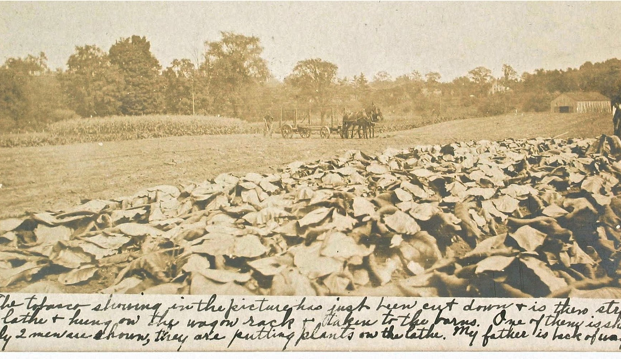

Floyd went farther than just writing about the goal; he planted 1/3 of an acre under cheesecloth. Covering fields with cheesecloth to soften effects from the sun had proven a successful strategy in Florida. Floyd planted half his small patch in CT-Havana seed and the other half in FL-Sumatra seed.

The CT-Havana tobacco was greatly improved by being under cloth but the leaves were too large and the veins remained huge by quality-Sumatran standards. It wouldn’t bring much more, if any, than what they were getting now. Sumatran seed brought the best leaves ever seen in Connecticut. Not as good as Sumatran, bet better than anything previous. But not good enough to bring the prices Sumatran did.

The following year, Floyd enlisted 14 farmers to test Sumatran leaf under cheesecloth on a total of 41 acres. For the publicity value, the plan was to sell what they grew at auction in New York City. As an aside, cigar tobacco is not normally sold at auction, and is sold in New York by wholesalers.

In 1902, Bureau Chief Milton Whitney’s GROWING SUMATRA TOBACCO UNDER SHADE IN THE CONNECTICUT VALLEY reported the results of Specialty-Agent Floyd’s two year study “aided by a corps of assistants cooperating with individual planters.” Whitney clearly stated the USDA would help in testing and developing a way to make Connecticut tobacco as marketable as possible.

“An attempt is soon to be made to secure a radical change in the type of the leaf by close planting, allowing many more leaves to the stalk, by very rapid growth, by shading, and possibly by irrigation. These experiments with Connecticut tobacco will be undertaken in the hope of producing a leaf approaching more nearly the Sumatra type of wrappers, this type generally accepted in this country as the standard for cigar wrappers.”

He went on to dangle a carrot of hope:

“With the intense cultivation that this will require it is quite possible these Windsor sands may be looked to for the finest wrapper leaf. “

But in the formal “Letter of Transmittal” published in the front of that report Whitney cautioned:

“A widespread interest has been taken in this work, and a general desire has been expressed to try to introduce this new industry in new areas in the different States. As will be gathered from this Bulletin [#20, 1902], the growing of Sumatran tobacco under shade involves a considerable outlay of time and money, and in my judgement it would be unwise to attempt a costly experiment of this character in areas where the soil survey has not indicated at least a reasonable chance of success. With the exception of a small area in Florida and southern Georgia where this type of tobacco was originally introduced and is still successfully grown, and of a narrow area of Donegal gravelly loam along the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, there are no other [[shadeleaf]] successfully grown, unless it may be on some of the soils of the tobacco districts of New York and Wisconsin; but as the soils survey has not as yet been extended to those places nothing definite can be said as to the possibility of raising Sumatra tobacco on such areas.”

USDA Agents like Stewart and Floyd believed if the start-up shade tobacco industry was to survive, they needed advice and example. To give themselves greater freedom to put their background into practice, both Stewart and Floyd resigned from the Department. Both left the Department of Agriculture with accolades. Both had exemplary records, research and analysis experience, publications, and the respect of their colleagues, though Floyd was the veteran, with more than 10 years more time in the Department.

This soils survey was one of the USDA’s greatest smash-hits in a long line of important contributions to American prosperity. The information gathered proved to be worth countless billions of dollars to farmers, miners, builders, naturalists, city and rural planners, the folks who design and build roads and many, many others. It was an outstanding example of a Federal Government project that cost a hefty sum but resulted in improved and expanded agriculture, millions of new jobs and a lot of silver and gold in the pockets of entrepreneurs and businesses nationwide.

Almost every former farmer turned to growing tobacco under shade in the Connecticut Valley. The step up from planting tobacco in the sun to planting it under cheesecloth is a huge one. But so is the increase in value of the crop. Their gamble was a good one. Tobacco and farmers flourished. Thousands of agricultural workers found steady jobs and the economy was prosperous. Floyd’s research and Stewart’s soil analysis made Connecticut shadeleaf a well respected alternative to Sumatra for dime cigars.

Upon his planting successes, Steward became a partner in the Whipple Tobacco Co, whose 400 acres he began to manage. Sometime thereafter, the Whipple Board sold the company and land to Hartman Tobacco Co., a grower and dealer in leaf. Stewart continued as partner and general manager of that firm until his death in 1935. Marcus Floyd had a similar career. After the USDA, Floyd managed the huge shade operation of the Connecticut Tobacco Corp. in the town of Tariffville. His plantation can be seen <here>.

Growing is only one step in preparing tobacco for market. It

It must be cured. Floyd first came to the Valley to evaluate early experiments in curing Connecticut tobacco in the same manner as did Cuba, Florida and Sumatra. He judged the results to be a slight improvement in uniformity of color, but not enough to sell for more money. When John Stewart began planting, tobacco curing involved hap-hazard subjection of leaves to burning charcoal in closed barns. This less-than-scientific approach all too often resulted in leaf unfit for market. Stewart began testing various combinations of temperature, time and humidity, the three variables in curing. The instructions he came up with would, if followed exactly, guarantee a good cure. It was widely adopted.

Stewart also improved fertilization techniques, demonstrated the value of cover crops and other innovations all of which he freely made public. To help make accurate information more available, Steward was a prime-mover in establishing the Windsor State Agricultural Experiment Station to study and improve tobacco culture in the Valley.

An ardent protectionist, Stewart lobbied for high import tariffs against Sumatran tobacco, but import taxes weren’t his only cause and concern. Stewart served as President of the New England Tobacco Growers Association and chaired its Legislative Committee. He aggressively championed Connecticut tobacco by serving on the board of directors of the Windsor Trust Company, serving as president of the Windsor Chamber of Commerce, and as president of the Plymouth Meadow Country Club. This scholarly and influential innovator and leader-by-example was a member of the the Wampanoag Country Club, a founding member of the Metropolitan District Commission of Hartford, and long-serving member of the Town Board of Relief,

Stewart proved his skills at more than agriculture. His chairmanship of the Windsor Town Board of Finance won him state-wide acclaim for sound fiscal management resulting in Windsor being known as “one of the best-managed towns in Connecticut.” He was also a member of the Connecticut Investment Managers Corporation, affiliated fraternally with Palisado Lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a member (and Past Master) of St. Mark's Masonic Lodge, and member of various higher Masonic bodies and the Order of the Eastern Star.

Though an avid golfer, Stewart remained an equally avid reader, keeping abreast with the latest in agriculture until his death at home at age 60 on May 27, 1935, following a brief and sudden illness. His death was a severe loss to the community.

Stewart was a smart, educated, personable doer who during his 30 year residency in Windsor was involved in nearly every facet of turning the disheartened and fiscally unsound Connecticut Valley into a prosperous farming community whose wrapper was respected around the world. He did so with modesty and with consideration for his fellow man. No small accomplishment.

John B. Stewart led a life of usefulness; the lives of many are better for knowing him. I am pleased to provide this brief introduction to the man and his deeds in the National Cigar History Museum.

Background manuscript and portrait provided the Museum by Joel Stewart, his grandson.