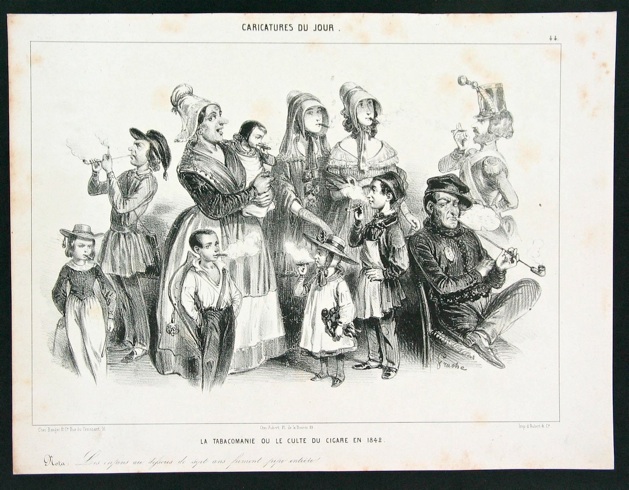

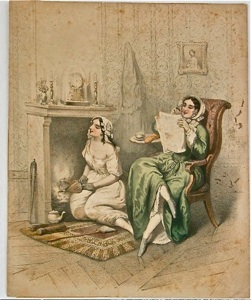

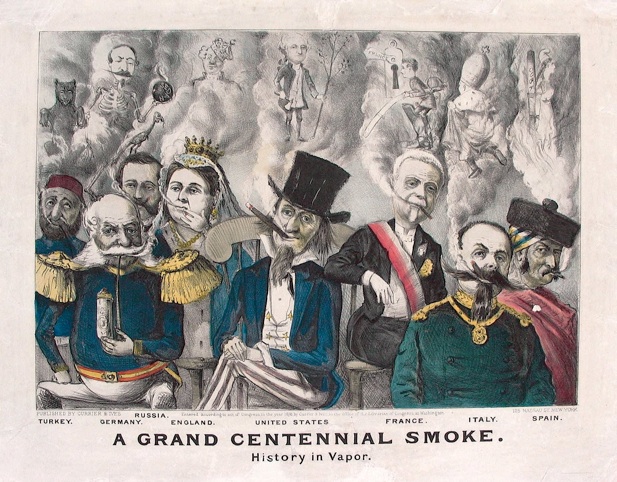

Typical of activities since homo-something-or-other came down from the trees, women have been an integral part of gathering, growing and processing food and other crops. That was equally true of the tobacco and cigar industries ever since there was such a thing. Women’s role in growing and manufacturing tobacco on vegas (farms) and in fabricas (factories) is subject for another exhibit. The focus of this exhibit is the first 150 years (1725-1875) of women portrayed as cigar smokers.

The earliest I’ve found so far is a 1732 print of “The Habit of a Malayan and his Wife at Bataria” published in A collection of Voyages and Travels by John and Awnsham Churchill in London. Both men carry pipes; the spouse is holding a cigar while being offered what is presumably a box of cigars or tobacco. The title indicates they both have a “habit” of tobacco use. Sadly, any text which originally accompanied the print is no longer present.

The print of “Angela, Femme de I’ile de

Guham” by A. Villain (c. 1839) leaves no doubt that Angela is smoking a cigar. The print is from Souvenirs d’un aveugle by Jacques Etienne Victor Arago (1790-1855). A French writer, artist and explorer, Arago joined Louis de Freycinet on his 1817 voyage around the globe aboard the ship Uranie. The then-Spanish Island of Guam was one of their stops. Nearly every traveler’s account from the late 18th and early 19th centuries refers to heavy smoking of cigars and papelitos or cigarros de papel (or other names for cigarettes) among women and children in Spanish colonies.

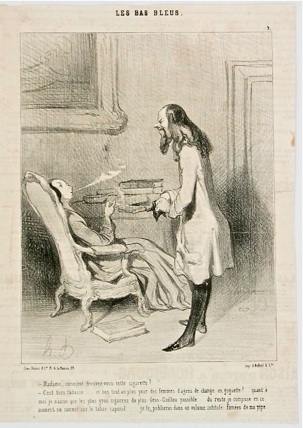

“How do you like this cigarette, madam?”

receives the reply “It has no taste. Only the wife of a stockbroker [symbol of the nouveau riche...TH] out for a good time could enjoy it. As to me, I only like the biggest and strongest cigars.”

This was printed a decade and a half before the introduction of small-leafed Turkish “Oriental” tobacco changed the nature of European cigarettes.