Louis Susini’s La Honradez

Cuban cigarettes & the 1st collectible

A National Cigar History Museum Exclusive

Text and illustrations © Tony Hyman, all rights reserved

Last modified: September 29, 2012

Louis Susini’s La Honradez

Cuban cigarettes & the 1st collectible

A National Cigar History Museum Exclusive

Text and illustrations © Tony Hyman, all rights reserved

Last modified: September 29, 2012

This Exhibit is based on reports of travelers 1850-1875, especially [1] A CIGARETTE MANUFACTURER AT HAVANA by Walter Goodman published in London Society magazine in 1872, [2] Chapter 10 in the widely known CUBA WITH PEN AND PENCIL by Samuel Hazard published in 1871 in Hartford, Conn., [3] HAVANA CIGARITOS by an anonymous reporter published in 1866 in All The Year Round magazine, [4] shorter minor reports by other writers, and [5] MARQUILLAS CIGARRERAS CUBANAS by Antonio Nuñez Jimenéz published by Tabacalera in 1989. Throughout the text, bracketed numbers refer to one of these sources.

Goodman reports that as the tour group was leaving the printing department, the foreman presented each of the ladies with a piece of Cuban dance music, upon the cover of which was printed a few words of dedication, accompanied by the lady’s own name in full.

Upon leaving the factory itself, visitors were asked to sign out. While adding their comments to those made by hundreds of dignitaries and other tourists, one of the Chinese workmen brought a package to one of the company officials who presented each visitor with a bundle of cigarettes emblazoned with a colorful wrapper bearing his own Christian and surname as a souvenir, a gimmick which impressed every factory visitor. [1,2,3,4]

Susini was very publicity conscious and made donations to various events and organizations. One of the company gift wrappers is seen left. It is not in the Hyman Cigar History Museum collection.

The Museum would like to own or photograph one of the gift labels given at the end of a tour that includes the name of the tourist. Certainly, someone kept one as a souvenir. If you have or know of one, please contact <tony@cigarhistory.info>

Hazard also points out that Susini & Son buys some cigarettes made by soldiers at the garrison of Havana, who roll in their spare time to augment low wages. He also claims casual workers throughout the town do the same. Since many famous cigar factories are known to use free-lance rollers who work at home or in small out-of-Havana factories when they fall behind in filling orders, it would be no surprise to learn Susini did the same, though Hazard is the only writer to make the claim.

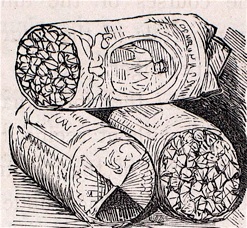

“The first ascent brings us to spacious store rooms where these cigarettes, and those already packed in bundles, are kept. The walls are literally papered with cigarettes in wheels, which look like complicated fireworks. As we move from one wheel to another we are invited to help ourselves to, and test he different qualities, which some of us accordingly do in wine-tasting fashion, taking a couple of whiffs from each sample and flinging the rest in the dust.” [1]

Later packaging for La Honradez

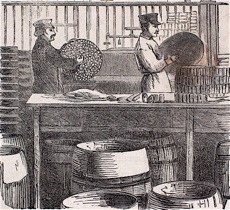

Interestingly, another correspondent [3] describes the packing area he saw as “hundreds of young women and children, blacks, mulattoes, and quadroons are employed in cutting and folding the paper, and in packing the cigarettes into bundles and gumming the wrappers.” Despite his omission of Chinese from the packing area, the unnamed author spends fully one-third of his article describing Chinese workmen, their dress, food, names, sleeping arrangements and religion in detail.

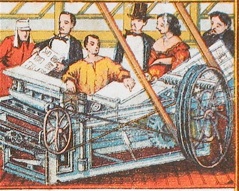

“The workmen who print these designs in colours, and mange a very elaborate steam lithographic press (made, as I deciphered from a cast-iron inscription, at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States), are a very odd kind of people indeed. They are not negroes, they are not mulattos, they are not quadroons, still less are they criollos or Creole Cubans, or Peninsulares, that is to say, European Spaniards. They are not precisely slaves; yet they cannot exactly be termed free. There is one of these odd workmen perched on a high stool by the side of the machine, and intent on adjusting the pins to the due and proper register of one of the coloured wrappers.” [3]

The workers were Chinese, who fascinated the anonymous author who wrote one-third of his article describing their characteristics. Hazard, too, had a good deal to say about the Chinese, apparently a novelty to mid 19th century Englishmen.

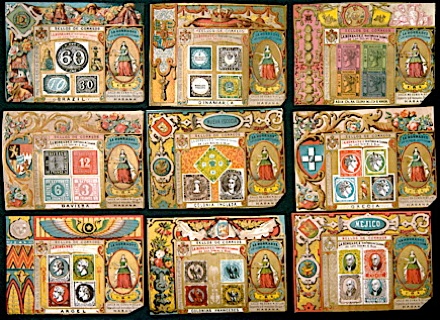

How many of these colorful labels were produced? The National Library in Cuba reportedly owns three albums containing 3,932 different cigarette wrappers from the 1850-1870 period with no assurances that is all that were made.

Susini creates the first tobacco collectible

Susini & Son is credited with first using continually changing sets of wrappers to thwart European counter-feiters who could fake a single standard unchanging label, but found it imposs-ible to keep up with labels that were used for only a few weeks, then changed.

Other Cuban cigarette companies were forced to redesign and frequently change labels to compete in the lucrative domestic market where collecting wrappers became a very popular hobby.

These 3.5” x 4.5” cigarette wrappers are historically important as they appear to be the first commercial package designed to be collectible, presaging cigarette card inserts by two decades.

Sets varied in size, from singles to more than 50. The range of themes was huge, history, travel, religion, uniforms, nature, fantasy, geography, fables, literature and more.

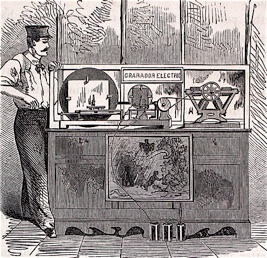

Magneto-Electrique Machine

“In the lithographic, drawing, and engraving room, I saw what I had never seen before in any other establishment, and which, I am told, is an entirely new discovery, -- he process of drawing on stone by chemical action and machinery. This is the machine known as the “Magneto-Electrique Machine,” the invention of Mr. E. Gaiffe, a Frenchman, and which took the prize at the World’s Fair and others. This machine, which has for its principal organ electricity, is the first that has been practically put in use, in this sort of industry, since the days of Franklin, the discoverer of electricity. The principle of the machine rests upon the interruption of the currents by a composition, or isolating ink, of which the design upon the matrix is composed.”

“By a circular motion of both the surface to be engraved on and the graver, and with the assistance of an electric magnet, pointed with a diamond, a complete and perfect drawing can be made without requiring any human assistance. The special advantage of the machine is, that henceforth the designer will be able himself to engrave his works without their passing through the medium of the engraver or the lithographer, who often, in following the text, cannot reproduce the peculiar touch of the artist.” [2]

Those writers who report taking the formal tour do not describe the same rooms in the same order or emphasis. This can be the result of different interests or different memories leading to omissions, or tours being re-routed according to the needs of production. All describe a huge operation joined by winding staircases and intricate passages. One reports beginning the tour in “the engine-room to glance at the steam power which works the machinery required in the different departments.” [1]

Hazard’s [2] tour begins in the offices, and moves from there to the carpenter shop, presumably part of or adjacent to the “engine room” described so briefly by Goodman above. The carpenter shop is where boxes, barrels, and crates were sawn, planed, nailed together and ultimately ink-branded by a steam press which incised the markings to various depths into the wood, replacing the hot iron method of branding familiar on earlier crates. Hazard calls it “a very ingenious process printed, giving a much better impression, without the roughness or imperfections of the branding-iron, while at the same time the operation is much more rapid.” He doesn’t mention it, but using a steam press to print marcas (brand identification) on wood was a lot safer, too. Technologically, Susini was ahead of the curve, in that cigar boxes in the U.S. were still hot-iron branded in the 1860’s.

After viewing this ‘maze of busy machinery,’ visitors enter the picadura (shredded tobacco) department, a site Goodman described as filled with “huge contrivances for pressing tobacco into solid cakes hard as brickbats; ingenious apparatus for chopping said cakes into various sized grains of picadura; horizontal and vertical tramways for forwarding the latter to their respective compart-ments. Near us is a winnowing chamber for separating particles of dust from the newly-cut picadura.” Upon entering the chamber via a spring door, Goodman reports everyone in his party was “seized with a violent fit of sneezing” because the air was filled with dusty particles of tobacco, like “standing within a huge snuff box!”

From there, tours pass through the stationery department where large sheets and thick reams of commercial paper was stored, ready to be used for brochures, catalogs, flyers, labels, wrappers, letterhead, and other commercial uses, all of which are printed in-house. Visitors are amazed to see all the types of cigarette rolling papers on hand. “A wonderful variety of rice and other paper is before us. There are two or three qualities of white, and endless shades of brown and yellow. Some are lightly tinted as the complexion of a half-caste. others are quadroon-hued, or of a yellow-brown mulatto colour. We are shown medicated and scented papers. The first of these, called pectoral paper, is recommended by the faculty to persons with weak chests; the last, when ignited, gives out an agreeable perfume.” [1]

In addition to the papers mentioned, Hazard adds coffee and corn being used for color and flavor, and the addition of various other scents resulting in a range of colors and scents for every taste. Honradez truly made expensive, semi-custom cigarettes for a world market.

From the stationery department, the next logical tour stop is the art department, “an airy studio, the sun’s rays tempered by screens of white gauze” on the windows. Visitors saw a number of Creole Spaniards at work busily designing on lithographic stone or woodblocks the fantastic picturesque designs for cigarette labels. Other Latins worked on gilding or illuminating labels. Further on was the printing operation where all the letterpress and lithography required in the establishment was accomplished. [2]

...We passed through numbers of barn-like rooms, vast and dim, where, squatting on the floor in groups, negro men, women and children were sorting the tobacco, stripping the leaves from the stalks, and arranging them in baskets for the chopping mills....Very great care seemed to be taken in the assortment of the leaves and the selection of the prime parts; and I was assured that the paper cigars of La Honradez were made from the choicest Havana Tobacco obtainable. They are, certainly, very delicious to smoke.” [3]

Tour of La Honradez

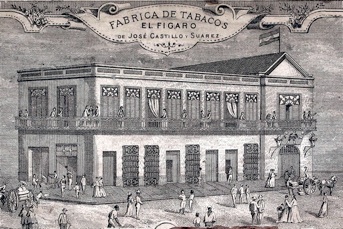

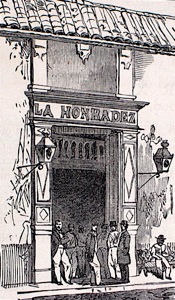

“I pause before the imposing factory of Louis Susini and Son, situated in a little Piaza in the Calle de Cuba. It is here that the best cigarettes, popularly known as Honradez, are manufactured. The exterior of the building with its marble columns reminding one of the Genoese palace, is worthy of attention. Above the grand entrance is the Honradez figure of justice, bearing the famous motto: Los hechos me justificarao -- my deeds will justify me.” [1]

“I think the place had been, prior to the suppression of the monastic orders, a convent. It was large enough to have been that, or a barrack or a penitentiary. The walls were amazingly thick; but the windows, few as they were in number, were neither so rare nor so thickly grated but that the odour of fresh-chopped tobacco came gushing through them...the air was laden with impalpable powder; that a sirocco of small cut speedily filled your mouth, ears and nostrils and the pores of your skin; and that your first salutation to La Honradez was a violent fit of sneezing.” [3]

Most visitors enter on San Ygnacio Street, and find themselves in a lobby surrounded by the company offices, where they are met by a polite and informative person who appoints a guide to show them around. The guide explains that everything in connection with cigarette making, except the growing of tobacco, takes place within the extensive premises. They are forewarned that a complete tour lasts most of the afternoon. All visitors are requested to sign in with their name and address, and are told they will be given the opportunity to add comments at the end of the tour.

“Having obeyed, copies of our autographs are made on slips of paper, and, by a mechanical contrivance in the wall, these are despatched for some mysterious purpose to the regions above.” [1] Susini, like many Cubans, was a technophile, fascinated by the latest in modern machinery, and had an internal telegraph connecting all departments. The ‘mechanical contrivance’ was probably a pneumatic tube system similar to that used today by many drive-through banks. Hazard commented on two other mechanical marvels in Susini’s hi-tech array: a “fire-machine” extinguishing system involving carbonic acid, hoses, and high pressure water as well as keyed-clocks requiring roving watchmen to punch in as they made their rounds through various departments.

Cuban cigarette companies

Cuban cigarettes of the 1860’s included Julian Rivas’s Figaro, Celestino Asay’s Florita, La Viuda (widow) de Garcia’s Mi Fama por el Orbe Vuela, Llaguno y Cia’s La Charanga de Villergas, Eduardo Guillos’s Para Usted, Anselmo del Valle’s H(iya) de Cabañas y Carvajal, La Dignidad, La Africana, La Belleza, Mendoza, La Rosarito, Barcenas y Posadas and, biggest and most famous of them all, Luis Susini & Son, maker of La Honradez (honesty or Integrity).

Susini’s worldwide fame made the factory a popular ‘must visit’ for natives and tourists alike. The company set daily tour hours, but its notoriously friendly staff did its best to accommodate tourists whenever they appeared at the “Royal and Imperial Factory of La Honradez.”

Cigarette Rolling

Cuban Cigarettes were called cigarros, cigaritos, papelitos, papeletas, papeletes, papelotes, papelillos and were distinctly different than Russian cigarettes made of Middle Eastern and Turkish tobacco with mouthpieces and filters. Cuban cigarros were made of finely chopped tobacco evenly rolled in a little square of very thin paper (more often than not made in France) and closed at each end “with a dexterous twist.” The end product was about an inch and a half long and an eighth of an inch thick, closed with a small joint-like folded twist at each end.

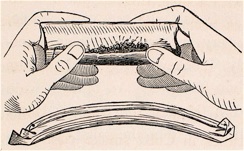

The art of rolling lies in there being just enough loose paper at the ends to make the twist and in there being an even distribution of uniform tobacco (or other substance) throughout the entire length. Smokes that are too tight or not evenly distributed with air pockets or bulges may be un-smokeable, or at least non-commercial. Customers demanded perfection because so many of them, especially in Spain, were experienced rollers. One mid 1860 author maintained the Spanish had been smoking cigarettes for 50 years and were very adept at rolling them. In contrast, he claimed, the English, Italians, Germans and French were klutzes dependent on factory cigarettes made of notoriously poor quality tobacco.

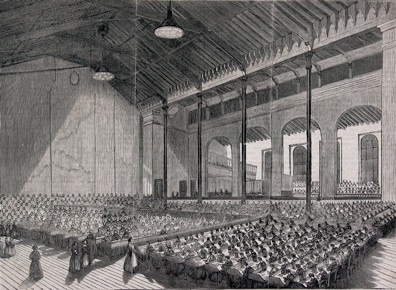

Cope’s cigar and cigarette factory in Liverpool was England’s largest, renown for hiring women and the handicapped. Cigarettes were popular long before the Crimean War, though soldiers returning from the mid-east did bring a taste for tiny Turkish leaf. Harper’s Weekly 1858 illustration.

Competition for smokers’ dollars was fierce. Mergers, buy-outs and business failures were commonplace. When the U.S. Civil War began in 1861, only 38 cigarrerias (cigarette factories) remained in Cuba, employing 2,300 workers, 1,300 of whom were rollers. The remainder were packers, printers, mechanics, managers and other support personnel. These figures don’t include the nearly 1,000 soldiers and prisoners who supplemented their income by rolling cigarettes for companies unable to keep up with demand. Factory output was a prodigious 307,500 packages of cigarettes a day.

By 1848, demand for Cuban tobacos (cigars) and cigarros (cigarettes ) had reached the point where more than 400 Cuban factories were cranking them out. Not all factories were licensed by the Crown to export, since typically half of each year’s official production of cigars and cigarettes was needed to supply Cuban residents. Cuban men and women were heavy smokers. Hazard observed “Wherever one goes in Cuba, the cigarette meets him at every turn, more so even than the cigar; for, in the cars, between the acts in the opera house, in the mouths of pretty women, between the courses of the dinner, and even, I might say, at the very portals of the church-door, one finds he delicate, fragrant, paper cigar.” [2]

Most Europeans did not share the distain of the lady in this 1844 Daumier print who dismissed cigarettes as something for the nouveau riche (“stockbroker’s wives”). “Give me a cigar,” she pleads.

Although a number of lithographic companies were in operation in Cuba by the 1860’s, and other cigarette companies bundled their product in similar wrappers, the only reports of in-house printing of wrappers and labels is at Susini’s factory.

Cigarettes remained popular with both sexes in Cuba for the next century and a half, right up to today. Later cigarettes included Partagas, La Legitimidad, Calixto Lopez, El Credito, Punch, Billiken and Trinidad y Hermano, the later being the most prolific user of insert cards, subject of another National Cigar Museum exhibit.

You can see a selection of La Honradez and other 1855-1870 cigarette labels <here>.

Hazard says the factory occupied the block from Cuba Street to San Ygnacio Street, corner of Sol, and illustrated the front door.

The hands are out of proportion in this drawing from Hazard. Actual cigarettes were about the length of your thumb.

Cuban cigarettes sold from two to ten times as much as those made else

where, so using holders

similar to substance

preserving roach clips

was common.

The hand is out of

proportion as the

cigarettes would have

been less than 2” long.

Paper wrapped wheels of cigarettes are packed in barrels for shipment overseas.

Despite this 1874 ad in an U.S. Trade publication, less than 5% of Cuban cigarette output found its way to the United States.

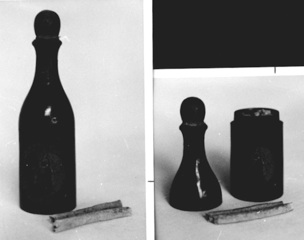

Not all La Honradez cigarettes were packed in paper wrapped packages. In the late 1800’s the company offered 10 cigarettes in small wooden bottles. Black in color, the bottles had paper labels bearing the classic Susini figure of Justice. The untwisted cigarettes are typical of late 19th century manufacture and believed to be original.

My apologies for the poor black and white photos taken 20 years ago. I’ve lost the bottle somewhere among hundreds of packed cartons.

Residents of the Caribbean have been smoking cigarettes since before the European invasion. Caribbean natives made theirs by wrapping chopped tobacco in corn, banana and other leaves. The Spanish replaced plant matter with small scraps of paper, whether home-rolled in Cuba or made in the giant Crown factories of the mother country. When Cuban ports were opened to international commerce in the early 1800’s, the world developed an insatiable craving for Cuban sugar, coffee and tobacco. Demand for Cuban cigarettes was so great, Cuba was forced to import large quantities of Kentucky tobacco through the port of New Orleans.

According to Jimenéz, Cuba exported just shy of 2,000,000 cajatillas (packages) of cigarettes in 1844. That’s a lot of smokes, though exactly how many can’t be determined since a Cuban cajatilla held anywhere from 10 to 50, depending on the tobacco, flavoring, and quality of paper used.

Philadelphia cigar label artist’s 1870 interpretation of Latin women smokers. He unintentionally makes the illustration a satire, depicting the woman on the far right as smoking two at once.

Figaro was the second largest maker of Cuban cigarettes, and one of Havana’s prestigious cigar makers. The factory was not open to the general public. Cigarette labels from Figaro, Honradez and other companies can be seen <here>.

Chinese lithographer as seen on an Honradez label picturing a factory tour. Note the tuxedoed gent inspecting a printed sheet with multiple images. One of the most desirable of the label series the company produced, this is not in the NCM collection. Courtesy of a private collector.