Fake Cigar Auctions 1881

A National Cigar History Museum Exclusive

© Tony Hyman

Uploaded October 10, 2010

Fake Cigar Auctions 1881

A National Cigar History Museum Exclusive

© Tony Hyman

Uploaded October 10, 2010

The number of persons who make a living by defrauding their fellow-creatures in New York City is greater, and the modes they employ for the attainment of their ends more varied, than many imagine. [New York City at that time was home to around 1,500 legally registered cigar factories and Heaven only knows how many small illegals; reasonable estimates claim between 500 and 1,000] Indeed, the lower quarters of the East Side [where a preponderance of immigrants lived], and even some of the down-town business centers, abound with swindlers who, while fleecing the public from morning to night, are by the very nature of their transactions comparatively safe from legal interference.

Foremost among this class for impudence and rascality are certain itinerant cigar and tobacco auctioneers. Wherever they find an empty store in a favorable location they hire it for temporary use. The auctioneer’s assistants are a sub-auctioneer and several professional “sharpers” or ropers-in, and it takes these men very little time to begin operations. All of them are resplendent in Bowery-cut clothes and false jewelry, as splendor seldom fails to impress the class that they victimize.

Their first step is to fit up the newly acquired store with glass cases and stands filled with cigar boxes, neatly labeled and pleasing to the eye. [Perpetrating a minor crime in a big city filled with much more important criminals, leaves these crooks reasonably free to operate in a single location for a month or more. Fraud victims who loose only a few dollars are notoriously reluctant to complain. Moving glass showcases is the antithesis of speed; they are heavy, cumbersome and fragile, requiring a horse and wagon and a few hefty men to move suggesting they stayed in a single building as long as possible or rented stores already equipped with counters and showcases. There were so many cigar factories and rollers in the city, a fresh supply of bad cigars was never more than a few anonymous blocks away.]

Once stocked, their second move is to hang out a red flag (traditional symbol of an auction in progress).

They then begin to entice customers by conducting a little sale all by themselves in which the sharpers play the part of an eager public, and display much activity in bidding for cigars and putting their money on the counter. [How many people are involved? Divvying up shares of the low profit isn’t going to leave much per person.] Soon the bait thus held forth is snapped at by a passing simpleton. [They better attract more than one simpleton. Frequent moves, rents, moving labor, horse and buggy maintenance and the half-cent to one-cent they pay per cigar all ads up. I suspect the author is using a figurative “one” to refer to a small crowd.] He enters the auction room and furtively watches the proceedings for a while, undetermined whether to invest his savings on the tempting ‘Havannas’ which are being struck down at such bargains. But before long he is approached by one of the sharpers posing as a buyer.

“Nice cigars, eh? Looks as if they can’t be beat, and there’s no mistake about them. Why, bless me, considering the prices they’re going for, a feller with some spunk, I should think, could sell ‘em again for double the money. Durned if I don’t feel like trying it myself anyhow.” [“Sell ‘em again” refers to the fact that retailers were frequently approached by brokers, jobbers, salesmen, even the owners of small factories, with offers of cigars. Traveler-smugglers were a fact of life. Tourists returning from the West Indies frequently brought cigars into the country without paying the high import duties, making them a profitable resell.]

With these words the speaker’s hand dives into the depths of his pockets. After a prolonged search, it reappears showing only a five dollar bill.

“The devil take it,” he murmurs. “There’s a fine lot there going for $10 or so, and I’ve already bought so much that I’ve only a five left.”

“But, I say, young man,” as a bright idea seems to strike him, “what if you and I go halves? Five dollars ain’t much for a man like you, and we can get twenty for that lot, don’t you know.”

The sale is meanwhile going on, the other swindlers still bidding feverishly for cigars and handing over money in payment. The youth hesitates a moment, but finally succumbs. His new acquaintance and business partner hastens to bid $10 on a lot of six boxes on sale. As if by magic the ardor of the other buyers abates; at least they do not outbid him. The youth produces his $5 -- perhaps his employer’s money, which he hopes to replace by a profitable disposal of his purchase -- and with the cigar-boxes under his arm struts forth triumphantly. It is unnecessary to add that the delusions he nurses are quickly dispelled when in attempting to sell them in a cigar store, he is confidentially informed that they are made of choice unadulterated cabbage leaves and brown paper.

Such swindles as the above are in daily occurrence all over the city, but although they have been brought to the notice of the Police Department no measures have been taken to remedy the evil. At the present moment a concern of this kind is fleecing the passers-by in Fulton Street.

To make it easier for the modern reader, a few minor changes in vocabulary, grammar and punctuation have been made.

Mock Auctions of Cigars

New York Tribune reprinted in the Oakland Daily Times, February 12, 1881

Modified for readability by Tony Hyman

Additional editorial notes in blue.

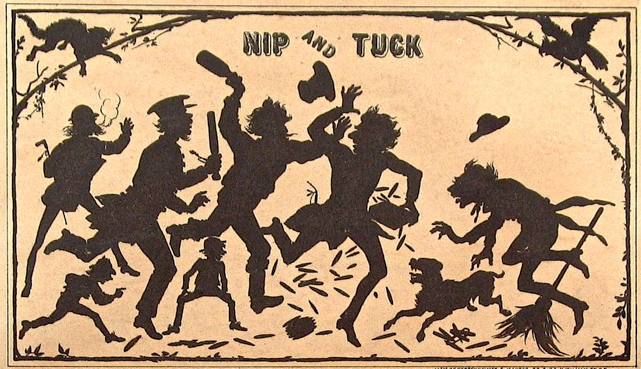

Chasing the malefactor