The first widely available premiums on the U.S. scene were tin tobacco tags. Like Susini’s cigarette wrappers in 1860’s Cuba, tin tags began as an attempt to thwart counterfeiting and grew into a popular collectible.

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War demand for Southern tobacco skyrocketed, and manufacturers large and small sprung up like weeds, all hoping to cash in. At that time both chewing and smoking tobacco was shipped in wooden crates called caddies, branded or labeled with the maker’s name. Once the crates were opened, every company’s tobacco looked pretty much alike. History has repeatedly demonstrated when a new product is in profitable high demand, retailers proliferate. The less scrupulous among them, as happened in the world of tobacco, took advantage of consumer inexperience by refilling empty caddies with inferior goods, thus cheating both the manufacturer and consumer.

The year of the 1876 Centennial, three,

and probably more, tobacco companies solved the problem of identifying their slabs and twists of tobacco by pounding one or more round wooden plugs into each piece before it left the factory. As the illustration (right) shows, they weren’t particularly fancy, but they were effective. Users of wooden plugs as tags in their products included H.A.H. & Co. in Chicago, P. T. Co. (Pioneer Tobacco) in Brooklyn and P. Lorillard, from New York City.

1878 trade card for H.A.H. & Co.’s GARDEN CITY plug tobacco. Ad above right is back of this card.

An ad from 1877 explains why multiple wooden plugs were used in a single one-pound brick of tobacco: “To help enable the dealer to secure every possible advan-tage, we have placed the Wooden Tags or Trademark at intervals throughout the entire length of the plug, which permits the retailer to cut the lump into small pieces to suit his customer, each piece holding its identity as though perfect plug in itself.”

Wooden tags were only used for a few years and are scarce today.

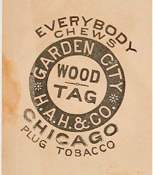

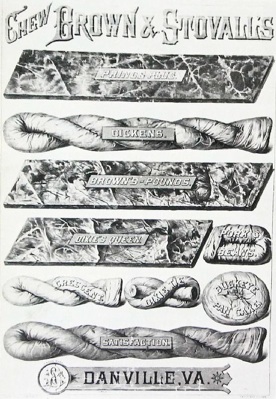

Trade journal ads from the 1880’s depict

some of the various forms in which tobacco

was sold, and how metal tags were applied.

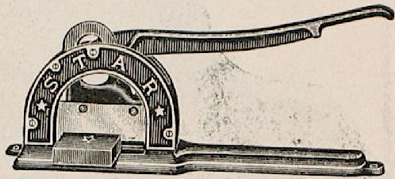

Tobacco plug cutters, like

seen here slicing a tagged

plug, soon adorned counters

everywhere tobacco was

sold. They were given away

free in exchange for large

orders (usually 50 lbs. or

more) and typically had the

company or brand name

prominently displayed.

Lorillard’s STAR cutter was

a freebie and one of the most

commonly found today. These

are NOT cigar cutters.

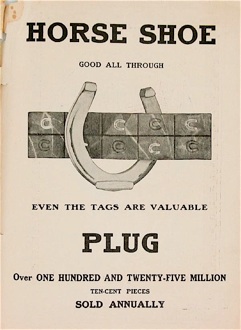

P. Lorillard was the first company to use tags made of tin to identify their products, but in one of those historic bad ideas, decided to put their tags under the outside leaf

Twist was an old-fashioned, but still popular, method of preparing leaf for sale as chaw or pipe. It was difficult to tell one maker’s twist from another until the introduction of tin tags. Twist tags often had one long prong instead of two shorter ones used on plugs.

which wrapped the brick, thus rendering it invisible until cut or bitten. This bad marketing idea led to chipped teeth and unhappy customers. Ben Finzer, owner of the Ben Finzer Tobacco Company in Louisville, liked the idea of tin tags, and became the first to put them on the outside of the slab or twist. Finzer tried unsuccessfully to patent the idea and placement. After the courts turned him down, tobacco manufacturers everywhere adopted the use of colorful tin tags. Because the tags were so inexpensive to make, custom brands and corresponding tags were easily created for retailers and wholesalers. Collectors have catalogued more than 12,000 different tags.

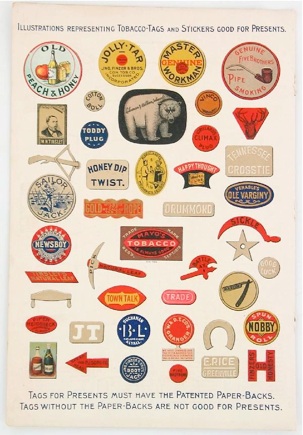

Tag collecting was a popular hobby as early as the 1880s with collectors in various regions of the country advertising in newspapers and trading hundreds at a time. Those who didn’t collect tags for aesthetic reasons accumulated them with a more practical motive.

A key strategy in the war for market supremacy was the offering of household items as premiums in exchange for tags. The man who couldn’t afford to buy his wife a set of silver-plated tableware, might be able to accumulate the 500 tags necessary to get six Rogers knives and forks for free. It was an age when hope sprang eternal.

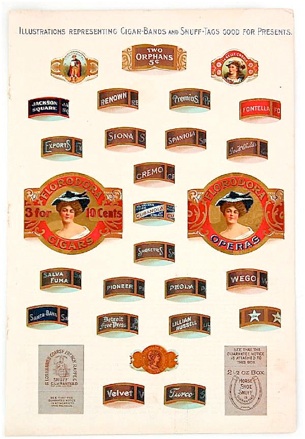

Center spread from the 1904 FLORADORA catalog showing the tobacco tags and cigar bands that would be accepted for redemption. Both the brands and the premium redemption company were acquired by the tobacco trust soon after and became part of United Cigar Stores redemption plan.

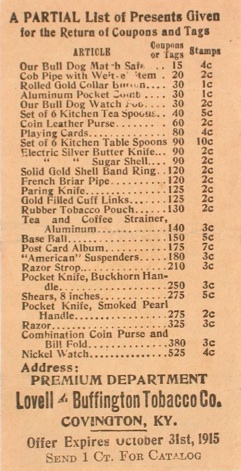

At first, offerings were sparse, as few as 20 items listed on the back of a trade card. Later came simple pamphlets without pictures. By the late 1920s, large illustrated catalogs offering thousands of items in all price ranges were given free or in exchange for a stamp or penny or two. Tags and bands and various coupons could be mailed in or delivered to redemption centers around the country.

One of the accidental strokes of genius in marketing, tin tags remained popular for four decades, ultimately made obsolete in the 1920s when machines began wrapping one-ounce bricks of plug in printed cellophane. By that time, paper coupons had largely replaced tags for premium redemption; coupons never took the place of colorful tin tags in the hearts of collectors.