CIGARETTE HISTORY

A Guest Article

CIGARETTE HISTORY

A Guest Article

The Early History of Cigarettes in America

Richard Elliott, Brandstand Vol 34: (Spring 2009)

When Christopher Columbus reached the West Indies in 1492, the natives greeted him with fruit, wooden spears and “certain dried leaves which gave off a distinct fragrance.” The Spanish sailors in Columbus’ crew appreciated the fruit but threw away the dried leaves not knowing what they were for. A few weeks later, while on a reconnaissance on the island of Cuba, two crewmen from the ship reported that they watched as natives wrapped the same type of dried leaves in maize and lit one end and inhaled the smoke from the other. Reportedly, one of the sailors tried a few puffs himself and soon became a confirmed smoker, probably the first European to do so.

Later explorers would learn that the new world was full of smokers and had been for hundreds of years. North American Indians prized tobacco and traded the valuable leaf regularly. While tobacco was usually smoked in simple pipes called “calumets,” Spanish explorers such as Cortez reported seeing Aztec and other Central American Indians smoking flavored reed “cigarettes” while the natives of Cuba reportedly rolled their leaf into cigars then as now.

Two main types of tobacco are involved in early history. In general, tobacco from Mexico North was a different variety than that grown in the Caribbean and South America. The tobacco used by North American natives that the English first smoked was a somewhat dreadful variety nicknamed “shoestring” by colonists. The Spanish, Dutch and Portuguese grew and smoked a milder broad leafed variety we think of today as Cuban tobacco, commercially grown on that island by 1535. As Dick points out, English colonists ultimately grew a hybrid tobacco using Caribbean seed. Tobacco is a very adaptable plant that can be grown anywhere and morphs into something different in just a few generations based on weather and soil. Bad conditions = bad tobacco that is commercially worthless. The soil-weather conditions gave Virginia, Carolinas, Maryland, and other southern tobacco states, a distinctive acidic tobacco favored by users of cigarettes, pipes and snuff. Tobacco grown in New England, the Caribbean, Philippines, Sumatra, India and South America is of Cuban origin, alkaline, and used for cigars.

By the mid 16th century, Portuguese settlers in Brazil began cultivating their own tobacco for export to Europe. In 1564, Captain John Hawkins and his crew introduced pipe smoking to England and over the next few decades the demand for American leaf grew significantly. Sir Walter Raleigh is credited with popularizing pipe-smoking at the English royal court not long after. A few decades later, John Rolfe brought South American tobacco seed to the Jamestown Virginia settlement and raised the first crop of “tall tobacco” in what is now the U.S. By the 1730s, the first North American tobacco factories had appeared in Virginia manufacturing snuff.

By the mid 19th century, cigarettes were gaining in popularity in Europe. In 1843, the French Monopoly began the manufacture of cigarettes, a form of tobacco consumption which up until then had a reputation as “beggar’s’ smokes” based upon the cheap smokes made from discarded cigar scraps in neighboring Seville, Spain for hundreds of years. Meanwhile in England, soldiers returning from the Crimean War brought with them a taste for Turkish cigarettes and soon this more “sophisticated” form of smoking was in vogue throughout the city of London.

Enter a third type of tobacco, radically different from the other two. Turkish, sometimes called “Oriental,” tobacco has a tiny leaf, only a few inches long, quite distinctly different in both form and taste from the often two foot long leaves used in cigar manufacture. You will read sources that incorrectly claim that cigarettes were introduced in Europe as a result of the Crimean War. As Dick points out, that is not true, although their popularity increased with the introduction of Oriental tobacco in the blends.

In 1856, one young veteran named Robert Gloag opened the first cigarette factory in London selling a brand called Sweet Threes. A few years later, another Englishman, Philip Morris, started making customized hand-made cigarettes at his tobacco shop and it wasn’t long before the Bond Street novelty spread to Fifth Avenue.

Many of the very early cigarette factories in New York were owned and operated by Greek and Turkish immigrants. One such company was founded in 1868 by the Bedrossian Brothers who blended Virginia and Turkish tobacco into numerous brands with metropolitan sounding names such as Non Plus Ultra, Petite Canons, No Name 10s, Ladies, and Neapolitans. Seeing an opportunity in the emerging market for cigarettes, tobacco man F.S. Kinney began cigarette production in New York City as well as at a factory in Richmond, VA, turning out brands with names like Full Dress, Sweet Caporal, Kinney’s Straight Cut and Sportsman’s Caporal also using a blend of Turkish and Virginia leaf. Kinney’s chief competitor in the New York market was Goodwin & Co. which sold nationally advertised cigarettes with folksy sounding brand names such as Old Judge, Canvas Back, and Welcome.

During this same post-Civil War period, William S. Kimball’s Peerless Tobacco Works of Rochester, N.Y. managed to capture an ever increasing share of the U.S. cigarette market with their Vanity Fair, Fragrant Vanity Fair, Cloth of Gold, Three Kings, Old Gold and Orientals brands. Meanwhile, yet another tobacco manufacturer, Allen & Ginter of Richmond, VA trademarked the brand names Bon Ton, Napoleons, Dubec, The Pet, Opera Puffs for the national market and an sold a brand called Richmond Straight Cut No. 1 both at home and internationally.

Along with New York City, Richmond, VA, and Rochester, NY, the city of Baltimore, MD became a center for cigarette manufacture in the early years with the entry of The Marburg Tobacco Company and Felgner into the race. Marburg aimed at the so-called “carriage trade” with their Estrella, High Life, Melrose and Golden Age brands while Felgner offered their own line of urban-sophisticated smokes with Sublime, Principal, Perfect and Herbe de la Reine.

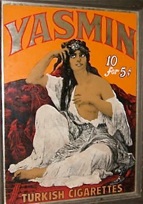

Combined, the Kinney, Allen & Ginter, Kimball, Goodwin, Marburg and Felgner firms became known as the “big six” of the cigarette industry by the 1870s as they gained control of 75% of national sales. There were, of course, hundreds of smaller cigarette firms operating out of back-room shops in most larger Northern cities during this era but their distribution capabilities were usually very limited. These operations typically employed fewer than a dozen Greek, Turkish or Bulgar rollers and turned out specialty “oriental” brands such as Khedive, Sultana, or Monopole. Their beautifully packaged cigarettes often featured silver and gold foil inner wrappings and a variety of sizes, shapes and mouthpieces. The prices charged for these specialty brands reflected the upper-class urban market that they were aimed at. Turkish Elegantes from Bedrossian Brothers sold at $1.00 for 20 and Huppmann Imperiales cost $1.20 for 20 at time when most national brands were priced at .05 cents for a box of 10.

Despite this rapid growth in sales of cigarettes in the 1870’s, it should be remembered that they were still considered a novelty and were for the most part an urban phenomenon. Americans were still very much attached to their pipes, cigars and chew. Historically, northerners had preferred cigars while “the chew” prevailed in the South. Pipe smoking was popular throughout the country although the choice of pipe was largely regional. As early as the 1820’s, John Quincy Adams had made “Havanas” respectable in New England society and “brown rolls” eventually became so popular that the Boston city fathers set aside a special area known as the “Smoking Circle” on Boston Common just for the cigar smokers. Meanwhile, throughout the South in the West, “the chew” prevailed. Of the 348 tobacco factories listed by the 1860 census of Virginia and North Carolina, only six were making smoking tobacco. The rest were making plug and twist tobacco exclusively. 1860 production figures for those two states alone amounted to 83,000,000 pounds.

By 1880, a young man in Durham, NC with a long family background in the tobacco business had come to the conclusion that cigarettes represented the future of his industry. James Buchannan Duke had grown up working with his father and brothers at the W.Duke & Sons Tobacco Company in Durham turning out Duke of Durham and Pro Bono Publico smoking tobaccos which were competitors of W.T. Blackwell’s world-famous Bull Durham Tobacco. Young “Buck” Duke saw the battle with Blackwell as a lost cause and in 1881 set his sights on the emerging cigarette business importing 125 experienced hand-rollers and a factory manager from New York to manufacture Duke of Durham Cigarettes. That same year, another young man named James Bonsack approached Duke with a cigarette-making machine he had invented. The young inventor had previously gone to the now “big four” companies but had been turned down because his machine was prone to break-down, plus there was a belief that consumers would never accept a machine made cigarette.

Duke put his top mechanics to work ironing out the bugs in the Bonsack machine, then signed a deal with the inventor. During his first year of production, using his team of imported hand-rollers, Duke had turned out 9,800,000 cigarettes. In contrast, using the Bonsack machines enabled him to produce 744,000,000 cigarettes in 1888. Duke soon added Cyclone, Duke’s Best, Cameo, Pedro, Town Talk , Crosscut and Pin Head to his stable of brands, the latter emblazoned with the words “These Cigarettes are Manufactured on the Bonsack Machine.” By lowering his production costs, Buck Duke was able to lower his price to 5¢ for a pack of 10. This was half the price of other major brands and the W.B. Duke Company soon had garnered a full 40% of the market. Gathering momentum, Duke stepped up the pace spending an unheard of $800,000 on print and billboard advertising in 1889 and sent salesmen across the country and around the world. In 1890, the “big four” companies, W.S. Kimball, Allen & Ginter, Kinney Bros. and Goodwin gave up the battle and joined W.B. Duke in forming The American Tobacco Company with a capitalization of $25,000,000 and James “Buck” Duke as President.

The new American Tobacco Company came to be referred to simply as “The Trust.” With Buck Duke at the helm, the firm proceeded to gain control of most of the cigarette production in the country along with much of the smoking tobacco and plug manufacturing as well. In true 19th century industrial-baron style, Duke built a vertical empire which controlled leaf suppliers, warehouses, box and foil manufacturers, and distributors. He bullied retailers and jobbers with threats of reduced commissions and drove out competition with cut-throat price wars. In the 1890’s American Tobacco bought out plug makers National Tobacco Works, P. Lorillard, Marburg and Butler-Drummond, channeling all of these firms into a new company called Continental Tobacco. They also struck a deal in 1899 with The Union Tobacco Company which was a rival combine and in so doing brought aboard the brands of former competitors Liggett & Myers, W.T. Blackwell and The National Cigarette and Tobacco Company. Finally in the same year, American Tobacco purchased a two thirds interest in R.J. Reynolds Company.

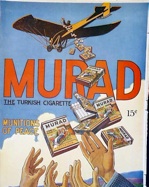

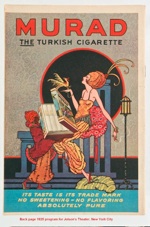

One area of the cigarette industry which Duke had problems conquering was the network of small tobacconists who were still hand-rolling specialty brands of cigarettes in back-room shops of New York City. He did buy some of the larger of these firms including M. Melachrino, S. Anargyros, Monopole, and Schinasi Bros., bringing on board their expensive Melachrino, Murad, Helmar, Mogul, Natural, Egyptian Prettiest, Egyptian Straights and Egyptian Deities all-Turkish brands. Duke also sold a line of cheaper “Turkish blend” smokes for the national market. This group included the Hassan, Mecca and Fatima brands.

Eventually, the trust absorbed most of the other major tobacco companies in the country including Mayo and Wright & Patterson of Richmond, Hanes & Brown of Winston, Beck of Chicago, Scotten-Dillon of Detroit, Bollman of San Francisco, Finzer of Louisville and Sorg of Middletown. By 1909, The American Tobacco trust controlled 86% of the national cigarette business, 85% of plug, 76% of smoking tobacco, 97% of snuff and 14% of cigar manufacture. The numbers were impressive by any standard the size of the American Tobacco empire also drew the attention of Teddy Roosevelt’s “trust busters” but that’s a story for another day. (R. Elliott).

The Emergence of the Standard Brands

Richard Elliott, BRANDSTAND Vol. 34 (Summer 2009)

James ‘Buck’ Duke’s ‘trust’ was like the dozens of other monopolies which had been built in oil, steel, lead, sugar, copper, cotton oil, distilling, linseed oil, cordage and other industries. Along with enormous industrial growth, this period of business empire building during the late 19th century was plagued by periodic economic downturns. The most severe of these depressions, which took place in 1893 and 1907, were devastating to millions of Americans from farmers to factory workers and many of those people came to blame “big business” for their woes. President Teddy Roosevelt responded to the call to “break up the trusts” with a series of suits against more than forty trusts and combinations between 1901 and 1909 including Duke’s tobacco combine.

Although the court ruled that there did not appear to be any increase in the price of tobacco products to the consumer as a result of the monopoly, the combine was judged to have restrained competition in violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and following confirmation of the decision by The Supreme Court in 1911, the company was to be divided into its’ component parts. Perhaps because he was the only person knowledgeable enough to perform the task, the court directed Buck Duke himself to dismantle ATC and restructure it into several smaller independents. The four major companies to emerge from the break-up were: American Tobacco, R.J. Reynolds, Liggett & Meyers and P. Lorillard.

The re-born American Tobacco Company retained a few cigar brands and most of its’ leading cigarette brands including Pall Mall, Mecca, and Sweet Caporal while Liggett & Myers received a substantial portion of the plug and snuff business along with Fatima, Home Run, American Beauty, Chesterfield and several other minor cigarette brands. Meanwhile, P. Lorillard was given all ‘Oriental’ brands including Turkish Trophies, Murad and Helmar and most of the combine’s cigar brands including Old Virginia Cheroots and Between the Acts among others. R.J. Reynolds received no cigarette or cigar brands in the breakup instead returning to its’ roots with twist and plug tobacco.

Although R.J. Reynolds Tobacco was the smallest of the four major firms which came out of the break up of Duke’s Trust, their company president, Richard J. Reynolds, was a feisty competitor and set his sights on doing battle with arch-rival “Buck” Duke and his American Tobacco Company on all fronts. Although Dick Reynolds had publicly stated that he would never use White Burley tobacco, which he considered inferior, he understood the need for compromise in the market and in 1907 he introduced a new pipe tobacco called Prince Albert which was based on that tobacco and by 1912 the brand had captured 15% of the national market. Reynolds also swore that he would never manufacture cigarettes which he felt catered to the decadent tastes of the worst elements of society. In fact he would never allow cigarettes in his own home.

Reynolds was, however, capable of adapting the changing marketplace and following the dissolution of the Trust moved quickly to join the race to enter the expanding cigarette market. He introduced a 20 for 10¢ brand called Osman which was based on latakia and other foreign leaf and 20 for 5¢ brand Reyno made with bright leaf. Neither of these brands did well perhaps due to lackluster promotional efforts and small advertising budgets. The next entry was Red Kamel, a more expensive 10 for 10¢ Turkish cigarette with a cork tip (which the Russians preferred for many decades by then). This too failed and was soon withdrawn. However, Dick Reynolds kept a fondness for the name and four years later when he struck upon the idea of developing a cigarette based upon a blend of Carolina Bright and highly flavored White Burley which could be made to taste like a more expensive Turkish blend, he chose the name Camel. Although there was very little Oriental leaf in the blend, the pack was adorned with pyramids, palm trees, sand and of course a camel. The words “Turkish & Domestic Blend” were accompanied by a disclaimer warning smokers “Don’t look for premiums or coupons as the cost of the tobaccos blended in Camel Cigarettes prohibits the use of them.” Camels were first introduced in Cleveland in 1913 and were an instant success. Smokers noted that they tasted like the Turkish blends but were lighter due to the presence of the Virginia leaf. Reynolds was encouraged by the reports from Cleveland and believed that the new brand had the potential to sweep the nation and gave the word to drop the plans for several other new brands and concentrate on Camels. He earmarked an unprecedented $1.3 million for sales efforts in 1914 with most of it going to Camels. The effort worked and by the end of that year new brand from RJR was one of the most popular in the country. The next year, the advertising budget grew to $1.9 million and sales continued to grow, making Camel the first true national brand sold in all 48 states. By 1917, sales continued to soar and by the end of the year, it was reported that one in three cigarettes sold in America was a Camel even with a reduced advertising budget of $700,000 that year.

Percival Hill who was Buck Duke’s successor at American Tobacco and his son George Washington Hill, Vice President in charge of sales, both took notice of Reynolds success with Camel. They recognized that the flavored white burley blend chosen by Reynolds along with the first real national advertising and distribution network which he set up for his Camel cigarettes represented the future for the tobacco industry. It took them a while but by 1915, they had given Charles Penn, VP of manufacturing, the task of developing a similar cigarette for American. Like Reynolds, who based his Camel cigarette on the Prince Albert pipe tobacco blend, Penn chose an old-line pipe tobacco from the ATC stable as his starting point. Lucky Strike had been a moderately successful pipe tobacco since 1871 so Penn set about adapting the white burley pipe blend to cigarettes. He added more flavorings, set up new cigarette making machines and soon was ready to invite George Washington Hill over to sample his new creation. According to company legend, Hill was entranced by the aroma of the new blend which reminded him somewhat of the smell of morning toast.

With a great fanfare and an expensive advertising campaign, Hill launched Lucky Strike cigarettes nation-wide in 1916. The slogan was “It’s Toasted” and the copy read “you know how toasting improves the flavor of bread and it’s the same with tobacco exactly”. The new brand was priced at twenty for 10¢ the same as Camels and was an instant success quickly gaining a 10% market share.

That market share declined slightly during 1918 partially because George Hill went off to France as a Red Cross major and later served in Washington with the Motor Transport Corps. He returned in 1919 to find that Lucky Strike had lost much of its’ early momentum with sales having slipped to 6% market share. He set about reinvigorating his brand with increased advertising and promotion. He was helped along with the general post-war upswing in sales as millions of doughboys returned the trenches of France having adopted the quick and easy “ready-mades” as their smoke of choice. In fact, the tobacco industry and the general public had made sure that America’s fighting men had plenty of free cigarettes in their kit-bags when they marched off to war and all of this was now playing into a general swing toward the “modern smoke.”

Liggett & Meyers had joined the cigarette race in 1912 with Chesterfield which was also based on a white burley blend and some foreign leaf for spice. The new brand with its’ British sounding name, Turkish blend and American tobaccos at first attracted little attention. But, when the company copied Reynolds’ Camels campaign and promoted Chesterfield as “ A balanced blend of the finest Turkish tobaccos with the choicest of several American varieties,” sales began to take off. By 1917, Camels, Lucky Strike and Chesterfield were dominating the cigarette market as sales of such traditionally popular Turkish brands as Murad, Omar, Mecca, Melachrino, Fatima, and Mogul tapered off. Likewise, the old-line Virginia Bright brands made popular by Duke such as King Bee, Home Run, Sunshine and even Sweet Caporal were in decline. The next three decades would become the ‘race of the standard’ brands as Luckies, Camels and Chesterfield battled for first place in sales.

When American troops had marched off to war in 1917, the tobacco companies and service organizations made sure they were well supplied with free smokes along with other small comforts such as candy bars, coffee and doughnuts; when the troops returned, many were confirmed cigarette smokers. This provided many thousands of new customers for the cigarette makers. The move from cigar and pipe to cigarettes was slow at first. but was helped along by a variety of different factors including lower taxes, changing social mores, improved cigarette making machinery, more widespread distribution network and concentrated advertising campaigns inspired by the success of Josh Reynolds with Camels.

The speeding up of society, new dances, shorter skirts, movies, the automobile and the “jazz age” in general encouraged cigarette smoking. Among the most defining change in social mores was the move toward the acceptance of cigarette smoking by women.

All three major tobacco companies were acutely aware of the changes taking place in the market during and immediately after WWI. The marketing men kept their eyes on the demographic statistics and the sales people took note of the cult of youth which was forming after the war. All were deeply interested in the female smoker, the largest untapped market in the nation. Earlier ads had hinted at the subject but usually in an indirect way as Turkish style cigarette ads pictured female models holding a pack of Moguls or Murads but none actually showed women smoking. But times were changing and men like George Washington Hill at American Tobacco set their sights on popularizing cigarette smoking among the newly liberated female population.

Some of Hill’s most famous campaigns for Lucky Strike evolved from the work of one of his most trusted advertising men, Edward Bernays. It was Bernays who hired a psychoanalyst to bolster his theory that some women regarded cigarettes as symbols of freedom and then hired attractive models to smoke Luckies in public. Later, he enlisted debutantes in his ads convincing them that they were striking a blow for women’s, freedom by endorsing smoking and Lucky Strikes in particular. When Hill expressed his concerns to Bernays that women might not be attracted to the dark green Lucky Strike packaging, the ad man set out to do nothing less than make green the most fashionable color. Working with friends in the fashion industry, Bernays paid for such events as Onandaga Silk’s “Green Fashion Luncheon” which featured green menus, green beans, asparagus salad, pistachio mousse glace and crème de menthe. There was also a “Green Charity Ball” sponsored by prominent socialite, Mrs. Frank Vanderlip and paid for by American Tobacco. Amazingly, green did become “the color” that year. Hill was pleased and Bernay’s got a raise. Another of Hill’s ad men, named Albert Lasker helped him develop perhaps his most famous campaign in the 1920s. Lasker’s wife had told him that her doctor suggested that she have a cigarette before meals to help suppress her appetite. The ad man took the idea to Hill and the famous “Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet” campaign was launched. The ads were so successful (and controversial) that they spawned several other memorable campaigns all developed around the theme of staying trim and attractive by smoking.

Women may well have joined the ranks of smokers in equal numbers during the Jazz Age without any prompting from tobacco men like George Washington Hill but we may never know for sure. (R. Elliott)

The Era of the Ten Centers

Richard Elliott, Brandstand Vol 34: (Spring 2010)

As the decade of the 1930’s began, the ‘big three plus one’ cigarette manufacturers enjoyed a commanding lead in sales. Although a few smokers preferred the old-line Turkish cigarettes such as Murad, Melachrino and Rameses, burley-based Camels, Lucky Strikes, Old Gold and Chesterfield accounted for an astounding 92% of all cigarette sales nationally. The lead was so comfortable by 1931 in fact, that the R.J. Reynolds Company decided to raise the wholesale price of Camels from $6.40 per thousand to $6.85. Lucky Strike, Chesterfield and Old Gold soon followed suit and the retail price of cigarettes moved from two packs for 25¢ to 15¢ a pack Reynolds defended the price increase as being a result of higher advertising costs but in fact the overall costs for manufacturing and distributing cigarettes had gone down for all four companies. As the economic downturn set in, both wages and the wholesale cost of leaf tobacco had dropped dramatically and profits were at an all-time high.

Probably coming as a surprise to the corporate directors at Reynolds, American Tobacco, Liggett &Meyers and Lorillard, it didn’t take long for the price increases to have a negative impact on their sales. In 1931, for the first time in over a decade, overall cigarette sales dropped, going from 124 billion to 117 billion units. Sales of Camels dropped an astounding 30%. Much of this was accounted for by the rise in sales for sack tobacco. For only a nickel, a penny-pinching smoker could buy a bag of Bull Durham and with the aid of some paper and a little practice, he could roll twenty perfectly good cigarettes. In retrospect, it is clear that executives at Reynolds and the other major firms misjudged the market as well as state of the economy in general but that is somewhat understandable given the commanding position which they were in at the time.

Then, in September 1931, Larus & Bros. a small Richmond firm, introduced a new brand called White Rolls based on the same blend of tobaccos in the standards but priced at 10¢ a pack. Even with very little promotion or advertising, the brand quickly picked up sales. The following month, Philip Morris followed suit by moving Paul Jones Cigarettes, which up until then was considered a regional brand with a small following in New England, onto the national market with a large advertising campaign. “America, here’s your cigarette, twenty for ten

cents” proclaimed the billboard and newspaper ads nationwide. The effects of these new “ten-centers” were beginning to be felt across the country and in March 1932, Brown and Williamson lowered the price of their Wings brand to 10¢ and promoted them heavily. Meanwhile, Liggett & Meyers joined the field by taking an old standby brand Coupon and re-packaging it into packs of ten for a nickel.

In June 1932, Woodford ‘Fitch’ Axton of The Axton Fisher Tobacco Company decided that the time was right for him to make a move and he did in a big way with a new “ten-center” called Twenty Grand. Promoted heavily, the new brand surged in sales almost immediately. Within three months, Twenty Grands were selling at a rate of 700,000 a day and Axton-Fisher couldn’t keep up with demand from retailers. Soon, the plant in Louisville was operating 24 hours a day and plans were underway for an expansion of the facility. The success of Twenty Grand and Wings, (which would briefly replace Old Gold as number four in national sales), led to an explosion in new low-priced brands. From PM subsidiary, Stephano Bros., came Marvels. Another PM subsidiary, Continental Tobacco, sold Black and White and Revelation cigarettes through their National Cigar Stands for the same low price. Scotten-Dillon of Detroit introduced Ramrod while Rosedor Tobacco of New York repackaged a 1920s brand called Bright Star as a ten-center. Christian Peper Tobacco Company of St. Louis brought out a 10¢ brand called Golden Rule. Flushed with the success of Wings, Brown and Williamson moved Avalon into the dime-a-pack category and promoted that brand widely. In 1935, Liggett & Meyers took another of their old brands, Sunshine, and turned it into a discount smoke. Finally, Lorillard entered the economy market in 1938 with Sensation which garnered only minor sales.

British controlled Brown & Williamson Tobacco Company of Louisville lacked the clout of the majors in the cigarette market

of the 1930s but they adopted an effective strategy to compete with their bigger rivals. Employing a sort of “shotgun approach” in 1932, the firm introduced Kool to compete in the menthol segment of the market,

Viceroy, a filtered luxury smoke, aimed at the urban market and a revamped Raleigh as their standard brand. The latter brand had been first introduced in 1929 as a premium cigarette with a luxury clamshell case and priced at 20¢. However, with the coming of the depression sales had dropped off sharply so Raleigh was given a new blend which was similar to the standards, a new package design, a lower price and something which set it apart from the rest of the field… coupons. Redeemable for numerous gifts from table lighters to flatware, the coupons came attached one to each pack with an extra four in each carton. This arrangement was attractive to both customers and retailers who could pocket the extra four coupons whenever they broke open a carton. While Viceroy sales were slow in the early years both Kool and Raleigh caught on with the public and earned a steady following.

In January 1933, The American Tobacco Company led the way in retreating from their earlier price hikes by lowering the wholesale price all the way down to $6.00 per thousand. It wasn’t long before the other three major cigarette makers followed suit and standard brands were back to two packs for a quarter at most retailers by late spring. But the market had been fundamentally changed with the proliferation of new brands and the big four standard brands would never again enjoy the almost total domination of the market which they once had.

“Loosies”

As the depression worsened, many Americans found themselves so short of cash that even the price of a pack of cigarettes was tough to scrape up especially just before payday. For those who couldn’t afford to buy a full pack, retailers began to offer individual cigarettes at a penny apiece. In the trade these loose cigarettes, which often were sold out of wooden boxes on the retailers’ counters, quickly became known as “loosies”. Although never acknowledged by the industry, the practice was popular not only with customers but also with retailers who could pick up an extra 5¢ on a pack by selling them this way. Although mostly a phenomenon of the depression, “loosies” survived well into the 1950s usually being sold to young smokers for whom the 35¢ then needed to buy a pack of cigarettes might be better invested in putting a gallon or two of gas in their cars.

Bibliography:

They Satisfy by Robert Sobel, 1978

Tobacco & Americans Robert K Heimann, McGraw-Hill 1960

Goodbye To All That Harris Lewine McGraw Hill 1970

Text by

Dick Elliott

President

Cigarette Pack

Collector’s Assn.

Join the CPCA and get its quarterly newsletter, BRANDSTAND,

which has been published since 1976. $10 per year.

This article has been modified slightly from the original appearing in BRANDSTAND.

Notes in blue italic are additions to Elliott’s text.

CONTACTING Dick

Email:

Phone:

(207) 985-4062

Snailmail:

86 Plymouth Grove Dr.

Kennebunk, ME 04043

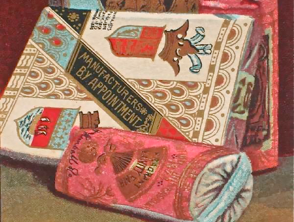

Until the mid 1880s cigarettes were sold in paper-wrapped bundles.

Cardboard push-packs holding 10 cigarettes or small cigars were introduced in 1884.

Wrappers from Cuban cigarettes by Susini, Figaro, and others were collected around the world in the 1860s, the 1st tobacco collectible.

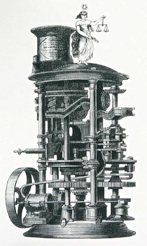

“The sensation of the Paris World Exposition of 1878” designed by Cuban Luis Susini could make 1600 cigarettes an hour.